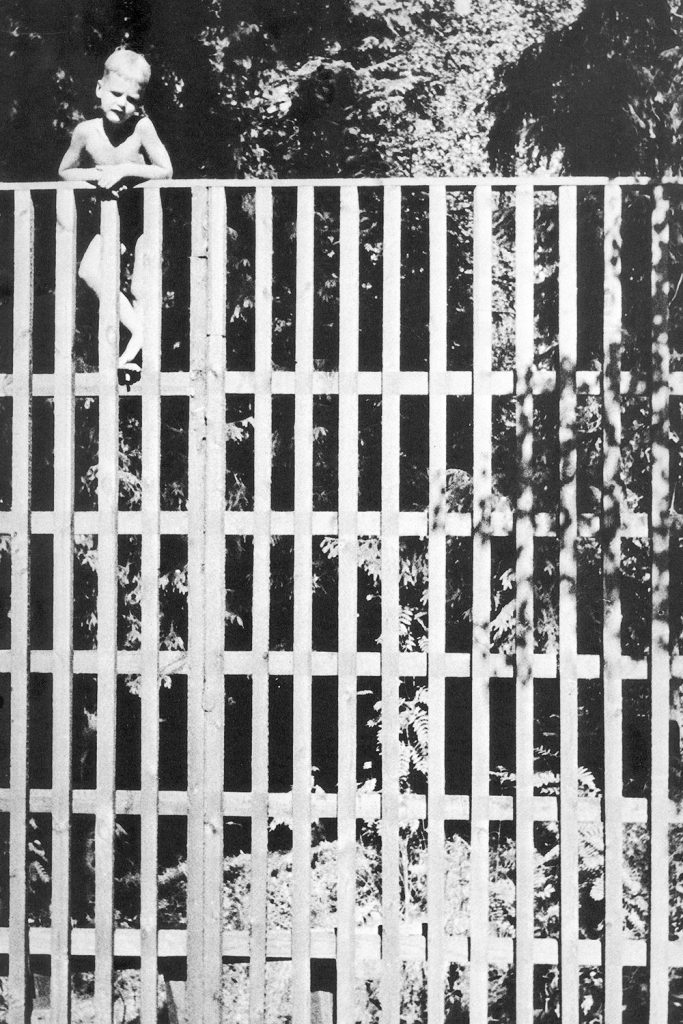

Al detenerme a reflexionar sobre el significado de términos como aprendizaje, formación, investigación, conocimiento o docencia, no puedo dejar de recordar esta fascinante imagen de un niño que trepa hasta lo más alto de la frágil cerca de madera que rodea su casa para poder descubrir el mundo que lo rodea. Se trata de una bella fotografía tomada por el artista polaco Winfrid Zakowski en la vivienda que Kaija y Heikki Siren se construyeron poco a poco, entre 1951 y 1960, en la pequeña isla de Lauttasaari próxima a Helsinki. En ella los Siren lograron resolver el difícil reto de conciliar la vida doméstica con el trabajo, dando lugar a una singular casa-estudio que fue creciendo conforme lo hacían su familia y sus responsabilidades profesionales, creando un hogar que los acompañó fielmente a lo largo de los años gracias a su notable capacidad de transformación. Estaríamos ante un caso concreto de lo que Alvar Aalto denominaba «la casa que crece», un concepto hondamente enraizado en la cultura popular finlandesa, revelador de la particular manera que los arquitectos de esta generación tenían de entender la relación íntima e inseparable que puede llegar a establecerse entre el habitar y el construir. El niño de la fotografía, supongamos que es Jukka Siren hijo mayor de la pareja también hoy arquitecto, escala la liviana valla que delimita el patio de la vivienda. Nos resulta fácil imaginar el esfuerzo y la sensación de riesgo que acompañan su corta pero emocionante aventura, impedimentos que se ven ampliamente superados por la inaplazable necesidad de asomarse a la bahía que se extiende al otro lado del cercado, por el intenso deseo de acceder al mundo que se despliega más allá de la seguridad y de la comodidad del hogar. Pese al ambiente estival y lúdico que transmite la escena, el gesto reflexivo y responsable del niño refleja la actitud de una persona que es consciente de estar realizando algo importante y audaz, al tiempo que su rostro nos muestra la satisfacción que se deriva de haber alcanzado una meta largamente perseguida. Pese a que no resulta evidente, a través de la imagen podemos comprender que la sencilla arquitectura de la cerca, resulta fundamental en este descubrimiento. Por un lado la pequeña separación existente entre los postes nos permiten adivinar la existencia otra realidad distinta, por otro los travesaños horizontales parecen haber sido dispuestos con el propósito de incitarnos a trepar por ellos, pero ante todo la ligereza casi textil de la valla nos traslada una sensación de provisionalidad que invita a superarla, a transgredirla, a ir más allá. En definitiva, lo que parece querer contarnos la fotografía, y probablemente lo más relevante de lo que uno aprende al aproximarse a estas delicadas arquitecturas nórdicas, es precisamente la trascendencia de los pequeños gestos cotidianos, su íntima conexión con la vida, su decisiva influencia en la construcción de nuestra experiencia, en la forma con la que miramos y entendemos el mundo.

Probablemente si al pensar sobre la docencia recuerdo con nitidez esta imagen es porque, a mi juicio, en ella se concentran los principales elementos que se dan cita en el proceso de adquisición, producción y transmisión del conocimiento. En definitiva el conocimiento es una «casa que crece», un hogar que nos acoge y acompaña a través del tiempo transformándose conforme transcurre nuestra vida. Un espacio íntimo y autobiográfico que construimos lentamente impulsados por un profundo deseo de saber, con el que damos respuesta a una necesidad vital de descubrir el mundo. Aprender requiere de una acción, ineludiblemente personal, que supone siempre un notable esfuerzo y en muchas ocasiones un riesgo intelectual, es una actividad que reclama que nos sacudamos la pereza y la comodidad, pero que al mismo tiempo nos aporta la intensa emoción propia del juego y de la aventura. Conocer es un empeño serio y decisivo que no puede abandonarse al errático devenir del azar y es precisamente aquí donde se impone la enorme responsabilidad que implica la docencia. Como ocurre con la ligera cerca de madera con la que los Siren decidieron delimitar su envidiable casa-estudio en Lauttasaari, la misión de la docencia es la de guiarnos y al mismo tiempo hacernos soñar con un mundo que se sitúa al otro lado, y su cometido último es poner a nuestro alcance los medios necesarios para que seamos capaces de alcanzarlo por nosotros mismos. Enseñar no es sino una fase más en el proceso de aprender, como también lo es investigar, y ha de afrontarse con la misma entrega y la misma pasión. Aprender, investigar, enseñar no deberían ser entendidos como hechos excepcionales circunscritos a breves periodos de nuestra biografía, tampoco como actividades exclusivamente relegadas al entorno académico. Deberíamos ser capaces de aprender de lo cotidiano y de forma cotidiana, esforzarnos por construir, habitar y compartir cada día nuestro conocimiento, con pequeños gestos y grandes descubrimientos personales como parece proponernos Winfrid Zakowski con su magnífica fotografía.

Publicado en Memoria docente curso 2015-2016 UCH-CEU

When I think over the significance of terms such as learning, training, research, knowledge or teaching, I cannot bare imagine this fascinating picture of a boy who climbs to the top of the fragile wooden fence that encloses his house so he can discover the world around him. It is an overwhelming photography made by the polish artist Winfrid Zakowski at Kaija and Heikki Siren’s house, built between 1951 and 1960; at the small island Lauttasaari, near Helsinki. On it, the Siren manage to solve the difficult challenge that is to combine everyday life with work, making a singular studio-house that grew at the same time it did both their family and professional responsibilities, creating a home which faithfully accompanied them through years, thanks to its remarkable transforming capacity. We would be in the specific case that Alvar Aalto called “growing house”, a concept deeply rooted in the Finnish folk culture, which showed the specific way that architects of this generation used to understand the intimate and inseparable relation that can be given between live and built. Say that the boy in the photo is Jukka Siren, the eldest son of the Siren couple, also now architect; he climbs the fickle fence which limits the house’s patio. It is simple for us to imagine the effort and the feeling of risk that goes along with his short but exciting adventure, impediments that are widely overcome by the unappealing necessity to lean out at the bay which extends at the other side of the fence, by the intense wish of reaching the world that unfolds further than the security and home’s comfort. Despite the festive and playfulness environment the scene transmits, the boy’s meditative and responsible gesture, reflects an attitude of someone who is conscious of making something important and bold, at the same time his face shows the satisfaction that develops from having achieved a goal long sought. Although it isn’t evident, through the picture we can understand the simple architecture of the fence, which is fundamental in this discovery. On one hand, the small separation between the posts allows us to guess the existence of a different reality, on the other hand, the horizontal crossbar seems to be arranged in order to incite us to climb it, transgress it and go further. Resuming, what the picture seems to tell us, and probably the most relevant of what one learns going near these delicate Nordic architectures, is precisely the transcendence of the small everyday gestures, its intimate relation with life, its decisive influence on the construction of our experience, the way with which we look an understand the world.

When thinking about teaching I clearly remember this picture, in my view, because in it the main elements that come together in the process of the acquisition, production and transmission of knowledge are given. Ultimately knowledge is a “growing house”, a home which welcomes and accompanies us through time changing as our life passes. An intimate and autobiographic space that we slowly build driven by a deep desire of knowledge, which gives response to the vital necessity of discovering world. Learning requires the unavoidable personal action that leads always to a remarkable effort and in some occasions to an intellectual risk, activity that demands to shake off laziness and comfort, and at the same time it provides us the intense emotion befitting of games and adventure. Knowledge is a serious and decisive aim that cannot be abandoned to the erratic evolution of chance and it is precisely here where the enormous responsibility that teaching implies imposes. As it happens with the lightness of de wooden fence with which the Siren decided to enclose their enviable studio-house at Lauttasaari, the mission of teaching is to guide us and at the same time to make us dream with a world that locates on the other side, where its last commitment is to put to our reach the necessary means for us to be capable to accomplish it for ourselves. Teaching is one phase on the process of learning, as it is researching, and they have to be faced with the same passion and enthusiasm. Learning, researching and teaching should not be understood as exceptional acts of short terms in our biography, and also such as activities exclusively relegated to the academic environment. We should be capable to learn from the everyday life, take effort in building, living and sharing our knowledge everyday, with small acts and great personal discovering as it seems to propose Winfrid Zakowski with his magnificent photography.

Published on teaching memorandum’s course 2015-2016 UHC-CEU